"I do it for my past self"

Have you ever thought about what it would be like if you could walk through one wall of your room just to reappear at the exact opposite one? What sounds impossible in our everyday life would be completely normal if we lived in a space called a 3-torus. Mathematician Jeffrey Weeks makes ideas like these accessible to the greater public. We talked with him about his younger self, his motivation for popularising mathematics, and the games he developed to make other shapes of space come alive.

First published in 1985, Weeks’ book "The Shape of Space" invites readers to expand their understanding of space without all the formalisms and technical terms, and instead through the medium of full-colour figures. Weeks is dedicated to teaching and constantly on the lookout for better ways to convey geometrical and topological ideas. This is what led him to start developing games that provide a fun and playful setting in which players are beamed into shapes of space like a 3-torus and asked to answer questions such as “What would you see if you lived in a universe like this?”. In the upcoming goMATH exhibition “The Shape of Space”, his games will be available for visitors to try out, helping them grasp new ideas of space.

Jeffrey Weeks, the goMATH exhibition in the form of a giant Möbius strip will be displayed in the Main Building of ETH Zurich. The Möbius strip is a very accessible phenomenon that is a source of fascination to every age group, including children. Do you remember when your own fascination for the shape of space started?

In high school, there were five or ten of us – in modern terminology, the nerds of the school – who would read books that were popularisations about maths and physics, or even philosophy, and pass them around. It was a very positive and fun experience. One book that I read was “Flatland” by Edwin A. Abbott. There was this idea of four-dimensional space and a hypercube. In general terms, I could see what it was getting at, but I couldn’t visualise it properly. I didn’t really grasp it, and I remember over the course of several weeks, as I was going about my life, this idea was turning around in my head. After a few weeks, I finally understood it and it was just such a joy. I think that was what sold me on mathematics: the idea that something seems difficult, you struggle and struggle, and finally you see it’s so simple and beautiful.

I think that was what sold me on mathematics: the idea that something seems difficult, you struggle and struggle, and finally you see it’s so simple and beautiful. Jeffrey Weeks

You work as a freelancer, which is quite unusual for a mathematician. Why did you choose this path?

I taught in a regular university position for a few years. Then my wife and I wanted to have a baby and I decided to become a stay-at-home dad for a few years, which I absolutely loved. As our son got older, I started doing some part-time contracts – for example, for what was then the Geometry Center in Minneapolis. I thought I would go back to teaching when my current projects were done but, as you might know, your current projects are never done – by the time one thing finishes, something else has already started.

Over the course of my career so far there have been three phases. The first phase was pure geometrical and topological research. The second phase began when interesting data about the cosmic microwave background came out and offered a chance to see whether the real universe could be finite or not. I worked in cosmological topology for about a decade. When that wound down, I devoted myself full-time to working on popularisations for the general public. And that is where things are now.

goMATH is an important programme that is designed to appeal to the younger generation and to women, and fire up their enthusiasm for mathematics. What motivated you to take part in the exhibition and work in the area of popularising mathematics?

I wanted to make maths more accessible. Basically, to share cool ideas with a lot of people. By the time I got to graduate school, I realised that there were some gaps in the library of popularisations. Among them were these beautiful ideas about space, like multiconnected space or curved space. The only available books were weighty tomes filled with lots of formalisms and technical terms. If you want to do research mathematics on these topics, you need all those technical terms. But for someone who wants just to learn the basic ideas, they are more of a barrier. That inspired me to take these beautiful ideas and strip away the formalisms to write a book that, in effect, my past self and my friends could have read. I guess it all goes back to the thought about what I and my friends would have liked to see and read.

I realised that there were some gaps in the library of popularisations. Among them were these beautiful ideas about space, like multiconnected space or curved space. Jeffrey Weeks

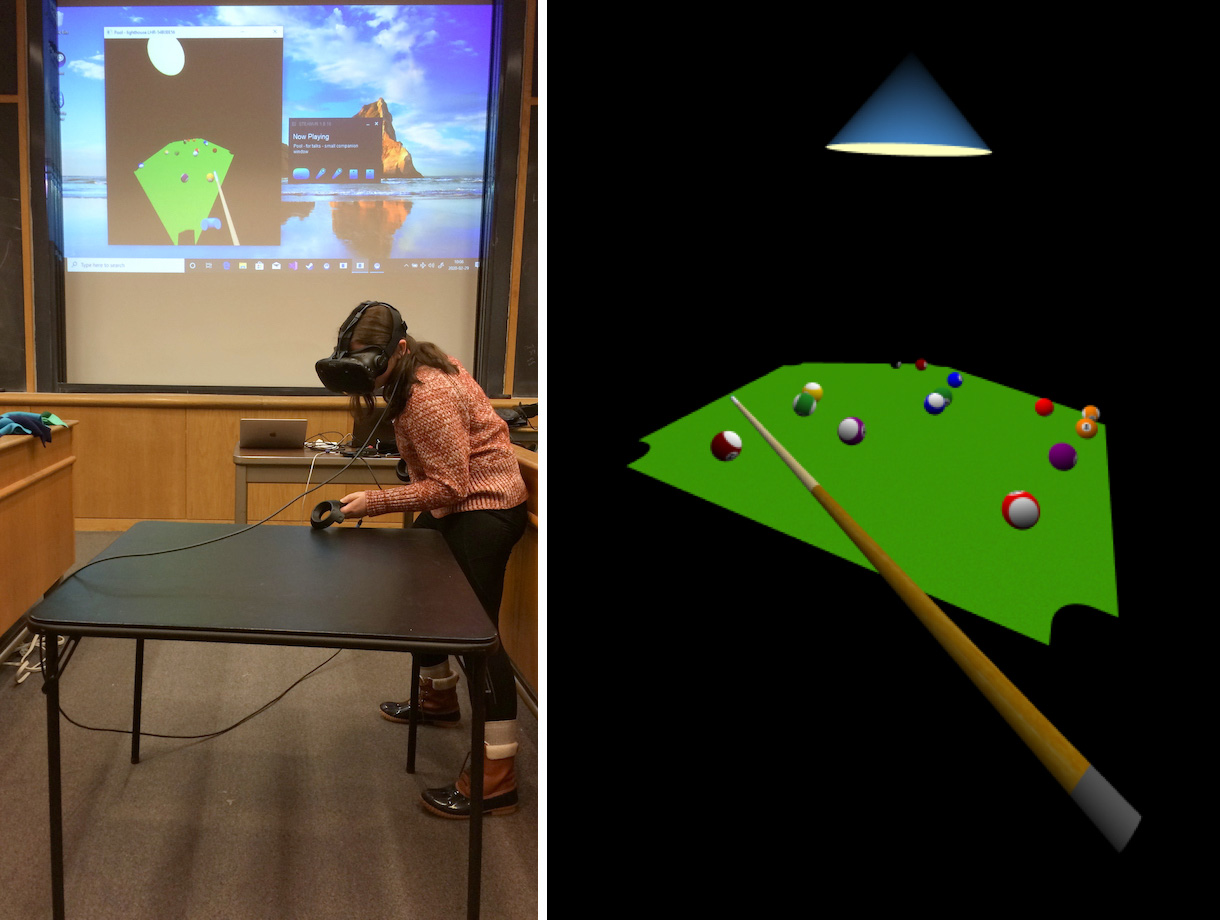

At goMATH, you exhibit the games you have developed yourself and give visitors a chance to play well-known games like tic-tac-toe or chess in other shapes of space such as a torus or a Klein bottle. Using virtual reality (VR), they can also immerse themselves in curved space for a round of billiards. Why did you start developing games like these?

I was trying to find progressively better ways to convey geometrical and topological ideas. Words alone are for sure the worst way to do it. Somewhat better are pictures – that is why my book is full of pictures. But better than pictures are animations where you can rotate things around and see them from different angles. Better still are interactive animations in which the viewer can decide where to go and what point to look at things from. Games on a touch-screen tablet, like the ones at goMATH, add a tactile component. But for something like curved space, the best thing is to put on VR goggles and really be there. That’s my motivation: to make these ideas come more alive. To create an experience where you can use your human senses to walk around and see different shapes of space.

How does a game come alive?

There are two elements you need for a successful game. Only two, but both are essential. First, it has to be fun to play, otherwise people won’t use it. Second, it needs to have some real substance, something of depth that people get some new insight from. I have a mental shelf full of all these interesting ideas and they kind of go in search of the right media to convey them. So, I look out for new technology and how I can make it an effective way of conveying an idea.

How did the games change your own understanding of space?

I had worked with curved spaces for decades and thought I understood them well. But even for me, the first time I put on the VR goggles and was actually in the curved space, there were surprises. I am almost embarrassed to say that. Because had I thought of it, I should have known what to expect. For example, when you play billiards in the spherical space, the billiards table seems to slope uphill. In the hyperbolic space it seems to slope downhill. If you had asked me, I should have been able to figure it out, but I never thought about that until I was there with VR. My mental picture of space changed, and I got a better intuition from the games.

Moreover, it made me appreciate more what we do in our everyday Euclidian experience: we can look at a table in perspective and still understand that it has to be a rectangle with four 90-degree angles. After playing billiards in curved space for a while, your brain gradually starts to make sense of it, and you get an intuition for this new shape of space. Our brain and visual system are flexible enough to get used it. But without VR, I think I never would have gained that sort of understanding of how things look as you walk around and how everything behaves.

The ideas you convey within your games are not just thought experiments, but are applied in fields like cosmology. How are your games connected to research?

The games on the iPads – the Torus Games – illustrate this idea that the universe could be finite but not have a boundary. It is still an open question. Even though the actual research on the shape of the universe has wound down now, there is still at least one group that is working on it. There were signs of a finite universe but there is no conclusive evidence. Because the speed of light is finite, we only see a certain distance, which might not be far enough to see repetitions that indicate a finite universe.

The curved space billiards game connects to the question of whether space is curved or not. Actual observations show that the part we see is close to flat – so it is either flat or it is slightly curved. And again, it comes down to a question of scale. If you walk out onto a frozen lake, for example, the ice surface on the lake follows the curvature of the Earth. The surface is part of a big sphere. But you are seeing such a tiny part of the Earth’s surface that it looks almost flat. It is the same deal with space: if the universe is a lot bigger than what we are seeing, then – even if it is curved – the part we are seeing seems close to flat.

The games on the iPads – the Torus Games – illustrate this idea that the universe could be finite but not have a boundary. It is still an open question.Jeffrey Weeks

Does that mean we will never be able to figure out the actual shape of the universe?

I’m not willing to say never but probably not within our lifetime. The reason people thought the universe might be finite has to do with the fluctuations in the microwave background. Researchers expected broader-scale fluctuations than the ones you actually observe. One explanation for why that would be is if the universe is finite. That means you cannot have fluctuations broader than the width of the universe. There is still one group working on finding a conclusive way of looking at things. However, in the future, there could be a completely new way of looking at things that might bring us a step further.

So the visitors to goMATH may learn a completely new way of looking at things by playing your games. What should they expect while they’re learning about the shape of space? Will their world view change completely?

With the help of the games on the iPads, they could expect to come away with an understanding that the universe does not have to be infinite. It can be finite and not have any edge. On the VR, though, their view of space might be completely changed. Our brain has only ever experienced Euclidian space and I definitely hope that entering some other space can be an eye-opener, showing that there are other possibilities than the Euclidian space we live in.